This is one of my favorite modern videos about the politics of sentencing. It is already a bit dated, but still is a great 90 seconds. Enjoy.

Sentencing Class @ OSU Moritz College of Law

A new home for an old class blog

recent posts

- Anyone have any distinct views on who Joe Biden should pick as US Attorney General?

- What data in the federal system would indicate the Biden Administration is drawing down the federal drug war?

- A final (too brief) foray into what metrics and data matter for assessing a sentencing system

- Reactions to our look behind the robes with federal sentencing judges?

- Are there any “offender characteristics” that you think must be considered at sentencing? If so, how?

about

-

Intriguingly, there has been a good bit of Ohio sentencing and punishment coverage in the Columbus Dispatch during our break this week, and I have linked some of the biggest stories via this post on my main blog. In addition, I encourage everyone interesting in Ohio non-capital sentencing law and policy to look around the website of the Ohio Criminal Sentencing Commission.

There are lots of notable (and intricate) materials to be found on the "Resources" sections of the OCSC website here and here. And I will likely assign for required or recommended reading later this month these particular OCSC documents:

-

As I mentioned last week in class, I am eager to receive any and all student feedback on the writing assignment I gave you for the first part of the semester. I trust no one found it too burdensome (though you should tell me if you did), and I am especially hopeful some will report in the comments if they found the assignment fun or at least useful/educational.

As always, feel free to post comments with or without your name as you see fit. (And please realize that I will take a lack of comments as a sign that there was not a strong disaffinity for this kind of assignment and that another similar small writing project before Thanksgiving would be just fine.)

-

As I mentioned in our last pre-break class, I highly recommend everyone join me in setting the DVR to record the new PBS three-part documentary "Prohibition." It begins airing tonight (Sunday, Oct. 2); I am hopeful that even those without TVs may eventually be able to watch the whole series via this official website. Here is a preview from that site:

As I mentioned in our last pre-break class, I highly recommend everyone join me in setting the DVR to record the new PBS three-part documentary "Prohibition." It begins airing tonight (Sunday, Oct. 2); I am hopeful that even those without TVs may eventually be able to watch the whole series via this official website. Here is a preview from that site:PROHIBITION is a three-part, five-and-a-half-hour documentary film series directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that tells the story of the rise, rule, and fall of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the entire era it encompassed.

The culmination of nearly a century of activism, Prohibition was intended to improve, even to ennoble, the lives of all Americans, to protect individuals, families, and society at large from the devastating effects of alcohol abuse.

But the enshrining of a faith-driven moral code in the Constitution paradoxically caused millions of Americans to rethink their definition of morality. Thugs became celebrities, responsible authority was rendered impotent. Social mores in place for a century were obliterated. Especially among the young, and most especially among young women, liquor consumption rocketed, propelling the rest of the culture with it: skirts shortened. Music heated up. America's Sweetheart morphed into The Vamp.

Prohibition turned law-abiding citizens into criminals, made a mockery of the justice system, caused illicit drinking to seem glamorous and fun, encouraged neighborhood gangs to become national crime syndicates, permitted government officials to bend and sometimes even break the law, and fostered cynicism and hypocrisy that corroded the social contract all across the country. With Prohibition in place, but ineffectively enforced, one observer noted, America had hardly freed itself from the scourge of alcohol abuse — instead, the "drys" had their law, while the "wets" had their liquor.

The story of Prohibition's rise and fall is a compelling saga that goes far beyond the oft-told tales of gangsters, rum runners, flappers, and speakeasies, to reveal a complicated and divided nation in the throes of momentous transformation. The film raises vital questions that are as relevant today as they were 100 years ago: about means and ends, individual rights and responsibilities, the proper role of government and finally, who is — and who is not — a real American.

-

As I mentioned in class, I am eager during the break to hear any and all feedback on the ways in which I have so far used this blog space to supplement/enhance class experiences and discussion. In the second half of the semester, I could:

- blog a lot more (or perhaps even less)

- provide more links to blogs/articles/cases we would not have time to discuss in class

- enable and encourage (or even require) some student blogging

- enable and encourage guest-blogging by real lawyers/judges working on sentencing issues

- be a lot more creative in this space (e.g., make more use of videos and other media)

Please let me know if you would find any of these kinds of changes to be especially intriguing or exciting And please know that I will interpret a lack of comments on this topic as a sign of contentment (and even great happiness) with the bloggy status quo.

-

As I mentioned in class on Tuesday, we will formally conclude our extended examination into the exercise and regulation of death penalty sentencing discretion on Thursday. In that class hour, I will ask some general and some specific questions about what we think about the law's modern efforts and (lack of?) success in regulating capital sentencing discretion. These questions may include:

1. Was Justice Harlan ultimately right in McGautha when asserting that providing useful/effective legal standards for the capital sentencing discretion is "beyond present human ability"?

2. Even if you think the development of capital sentencing discretion standards are a good idea, should such standards be mandated by constitutional rules?

3. Is the effort at regulating death sentencing decision-making by juries and judges doomed to some measure of failure because there is little or no regulation of death sentencing decision-making by prosecutors?

4. Are modern experiences with capital sentencing discretion and regulation have facets that are unique to application of the punishment of death, or are there important lessons to be learned for all forms of sentencing practices and types of punishment?

I could go on and on with questions, but you get the idea. And, though we will discuss these and other matters in class on Thursday, I am eager to hear any and all thoughts on these topics now in the comments (and/or throughout our up-coming Fall Break).

UPDATE: As detailed in this post on my main blog, former Justice John Paul Stevens has recently made some interesting comments lamenting his 1976 vote to approve the special way Texas uses special questions to guide death penalty sentencing discretion.

-

As the casebook highlights, Kentucky in 1998 enacted the first statutory response to the McClesky ruling through its Kentucky Racial Justice Act. And just two years ago, North Carolina followed suit through the enactment of the North Carolina Racial Justice Act.

There has not been much litigation over the Kentucky RJA because that legislation was expressly made notretroactive so that it could not be applied to any person sentenced to death in Kentucky before July 1998. (A short 2010 law review article on the Kentucky RJA can be found at this link.)

In contrast, many defendants on North Carolina's death row right now have pending claims based on the NC-RJA because that statute provided a one-year window for previously sentenced defendants to file a claim based on the NC-RJA. All but a few death row defendants did file claims based on the NC-RJA, though litigation on particular defendants' claims have so far been stalled in the North Carolina lower courts. (A long, now-dated 2010 law review article on the NC-RJA can be found at this link.)

Though there is much to discuss concerning McClesky and the Kentucky and NC RJAs, I wanted here to set forth my working draft of a proposed "Ohio Racial and Gender Justice Act" for discussion in the comments and in class. So here goes (with language based in large part on the NC-RJA):

1. No person shall be subject to or given a sentence of death or shall be executed pursuant to any judgment that was, in any part or in any way, sought or obtained on the basis of race or gender.

2. A finding that race or gender was in any way any part of the basis of the decision to seek or impose a death sentence may be established if the court finds that race or gender was in any way any part of decisions to seek or impose the sentence of death in the county, the prosecutorial district, the judicial division, or the State at the time the death sentence was sought or imposed. Evidence relevant to establish a finding that race or gender was in any way any part of decisions to seek or impose the sentence of death in the county, the prosecutorial district, the judicial division, or the State at the time the death sentence was sought or imposed may include statistical evidence or other evidence, including, but not limited to, sworn testimony of attorneys, prosecutors, law enforcement officers, jurors, or other members of the criminal justice system or both, that, irrespective of statutory factors, one or more of the following applies:

(A) Death sentences were sought or imposed any more frequently upon persons of one race or gender than upon persons of another race or gender.

(B) Death sentences were sought or imposed any more frequently as punishment for capital offenses against persons of one race or gender than as punishment of capital offenses against persons of another race or gender.

(C) Race or gender was in any way any part of decisions to exercise peremptory challenges during jury selection.

3. The state of Ohio has the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that race or gender was in any way any part of decisions to seek or impose the sentence of death in the county, the prosecutorial district, the judicial division, or the State at the time the death sentence was sought or imposed.

4. If the court finds that race or gender was in any way any part of decisions to seek or impose the sentence of death in the county, the prosecutorial district, the judicial division, or the State at the time the death sentence was sought or imposed, the court shall order that a death sentence not be sought, or that the death sentence imposed by the judgment shall be vacated and the defendant resentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

5. This act is effective when it becomes law and applies retroactively.

The language in bold and italics within my proposed Ohio statutory language highlights my tweaks to the Kentucky and NC RJAs, both of which concern only race and seem only concerned with race as a "significant" capital sentencing factor. In addition, both acts place the burden on defendants to prove race was a significant factor in their cases. As my draft reflects, I am very eager to ensure that neither race nor gender plays any role in the pursuit or imposition of the punishment of death. In service to that goal, my proposal puts the burden on the state of Ohio, once a claim is brought under this Act, to prove convincingly that neither race nor gender played any role in the death sentencing process.

Thoughts? Who is willing to co-sign this bill as proposed? I am open to friendly amendments and also eager to hear if any legislators oppose this effort to eradicate the problem identified in McClesky through a legislative response.

-

Sorry to have played an (evil?) game of guess the murderer at the end of class yesterday, but I think the story of Terry Nichols encounters with both the federal and Oklahoma capital punishment system provides a useful reminder that some (many?) high-profile US mass murderers can escape a death sentence in various ways. Via his Wikipedia entry, here are the basics of Terry Nichols' crime and how he managed avoid a death sentence:

In 1994 and 1995, [Terry Nichols] conspired with [Tim] McVeigh in the planning and preparation of the Oklahoma City bombing – the truck bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma on April 19, 1995 which claimed the lives of 168 people including 19 children.

After a federal trial in 1997, Nichols was convicted of conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction and eight counts of involuntary manslaughter for killing federal law enforcement personnel. He was sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole because the jury deadlocked on the death penalty. He was also tried in Oklahoma on state charges of murder in connection with the bombing, and was convicted in 2004 of 161 counts of first degree murder, which included one count of fetal homicide, first degree arson, and conspiracy. As in the federal trial, the state jury deadlocked on imposing the death penalty. He was sentenced to 161 consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole, and is incarcerated in ADX Florence, a super maximum security prison in Florence, Colorado. He shares a cellblock that is commonly referred to as "Bombers Row" with Ramzi Yousef and Ted Kaczynski.

As I mentioned in class, Jeffrey Dahmer (who killed at least 17 people in Wisconsin) and Dennis Raeder(the BTK Killer, who killed at least 10 people in Kansas) and Joel Rifkin (who kiled at least 17 people in New York) and David Berkowitz (the Son of Sam, who killed at least 6 people in New York) are just some examples of some infamous modern serial killers who escaped a death sentence because they committed mass murder in states without the death penalty at the time of their crimes.

In addition, some other modern mass murderers like Gary Ridgway (the Green River Killer who killed at least 49 people in Washington) and Charles Cullen (who killed at least 29 people in New Jersey and Pennsylvania) and Ronald Dominique (who killed at least 23 people in Louisiana) are just some examples of some infamous modern serial killers who escaped a death sentence because, after committig mass murder, they were able to cut plea deals with state prosecutors in order to take the death penalty off the table.

Does this kind of information make you more sympathetic (or less sympathetic) to claims of unconstitutional or just unfair sentencing disparity often made on behalf of folks who are sentenced to death in many states for only one murder (like Warren McClesky and Troy Davis)?

In light of this information, might you support a new federal death penalty law that defined the murder of,say, five or more people over an extended period of time to be a form of terrorism and thereby readily subjecting all of these sorts of serial killers to possible federal capital prosecution if/when state authorities are unable or unwilling to seek a death sentence for a mass murderer?

-

As a few folks have already noted in comments to a prior post and as this lengthy Atlanta Journal-Constitution article reports, this morning the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles declined to commute the death sentence of Troy Anthony Davis. A couple quick thoughts and questions to set up a discussion here (and perhaps also in class):

1. I was wrong in my prediction that the Georgia Board would grant clemency (and I have already proudly admitted this at my SL&P blog in this post). Not that you needed proof that I can be wrong, but I hope you all realize that I am never ashamed to be wrong and I often then become eager to figure out why.

2. Troy Davis got every layer of traditional appellate review of his original death sentence as well as (many) additional ones. Should this fact make us more comfortable with his pending execution or more concerned about the value of lots and lots of review of death sentences?

3. What should persons who are genuinely concerned that the Georgia might execute an innocent person tomorrow do now? What if those persons work for the US President or Georgia's governor?

4. Is the Davis case getting so much attention only because of innocence issues? How much of a role do you think race and geography is playing here? If all the offense facts were the same, but the state about to execute Davis was Ohio and Davis was white, do you think the case gets as much attention? More?

I have lots of coverage of both the history and current doings in the Davis case in this posts from my SL&P blog:

- SCOTUS orders innocence hearing in Troy Davis case (Aug 2009)

- A year after SCOTUS intervenes, Troy Davis innocence hearing about to start (June 2010)

- "Innocence claim rejected: Troy Davis loses challenge" (Aug 2010)

- Will third time clemency hearing be the charm for Troy Davis on eve of his latest execution date?

- The latest news (and helpful background) on the Troy Davis case

- "Slain officer's family calls for Troy Davis' execution"

- Georgia board denies clemency to Troy Davis

UPDATE: The official statement from the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles is short and available at this link. Here is the text in full:

Monday September 19, 2011, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles met to consider a clemency request from attorneys representing condemned inmate Troy Anthony Davis. After considering the request, the Board has voted to deny clemency.

Troy Anthony Davis was convicted in 1991 of the murder of 27-year old Savannah Police Officer Mark MacPhail. On August 19, 1989, MacPhail was working in an off-duty capacity as a security officer at the Greyhound Bus Terminal which was connected to the Burger King restaurant located at 601 W. Oglethorpe Avenue. At approximately 1 a.m., on that date, Officer MacPhail went to the Burger King parking lot to assist a beating victim where MacPhail encountered Davis. Davis shot Officer MacPhail and continued shooting at him as he lay on the ground, killing MacPhail. Davis surrendered on August 23, 1989.

Davis is scheduled to die by lethal injection September 21, 2011, at 7 p.m., at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison in Jackson, Georgia.

-

One (of many) interesting and valuable components of Ohio's modern death penalty system is the fact that the Ohio General Assembly has, by statute, required the Ohio Attorney General to produce an annual report on capital punishment regarding individuals who have been sentenced to death since Oct. 19, 1981. The last four such annual reports are all available on-line via this webpage, and I highly encourage students to at least review quickly the most recent of these reports report (which is the 2010 Capital Crimes Report released in April 2011 available at this link).

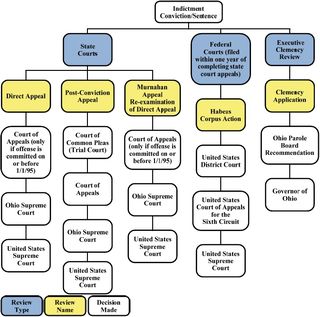

One (of many) interesting and valuable components of Ohio's modern death penalty system is the fact that the Ohio General Assembly has, by statute, required the Ohio Attorney General to produce an annual report on capital punishment regarding individuals who have been sentenced to death since Oct. 19, 1981. The last four such annual reports are all available on-line via this webpage, and I highly encourage students to at least review quickly the most recent of these reports report (which is the 2010 Capital Crimes Report released in April 2011 available at this link).The latest annual report will not only help you figure out how Ted Kaczynski might fare under Ohio's laws (see pp. 4-7 in the 2010 report), but also highlights the many fora for review of Ohio death sentences (see pp. 8-12 in the 2010 report, where the chart reprinted here appears at the end). The 2010 report also has an extended discussion of DNA testing procedures and results for those sentenced to death at pp. 15-22. The report also provides this (now slightly dated) statistics about the application of the modern Ohio death penalty:

Since 1981, Ohio has issued a total of 310 death sentences….

As of [the end of 2010], a total of 41 inmates have been executed under Ohio’s current law….

[And] a total of 14 inmates received a commutation of his death sentence to a sentence less than the death penalty….

[And] a total of 20 inmates died prior to imposition of the death penalty. This includes inmates who died of natural death and suicide….

[And] a total of 8 inmates were found ineligible for the death penalty dueto mental retardation (aka “Atkins” claims)….

[And] a total of 7 death sentences were vacated and remanded to trial courts for re-sentencing, which could result in imposition of the death penalty again … [and] there was 1 case pending retrial….

[And] 64 death sentences were removed as a result of some form of judicial action beyond the cases already mentioned….

[And] a total of 155 death sentences remained active, including those currently pending in state and federal court [including] seven individuals [who] received a death sentence and were added to death row [in 2010].

As was true following my prior national data dump on executions in this post, I welcome and encourage comments on what lessons we might take away from this Ohio modern death penalty data and history. Also, I encourage early thoughts about whether these data should suggest a particular agenda for the Ohio Chief Justice's newly form Joint Task Force to Review the Administration of Ohio’s Death Penalty (discussed in this press release and constuting a partnership between the Supreme Court of Ohio and the Ohio State Bar Association “to ensure that Ohio’s death penalty is administered in the most fair, efficient, and judicious manner possible.”)

-

To give you a focus for examining modern death penalty statutes, the casebook encourages thinking about how you might help represent Ted Kaczynski if he were to be prosecuted under the applicable death penalty statutes in Texas and Florida. Though not in the text, you should also consider how you think Ted might fare under Ohio's death penalty statute and its distinct specification of aggravating and mitigating circumstances. (Ignore for purposes of this exercise that these states would not likely have jurisdiction.)

For a lot more information about "your client," here is a massive Wikipedia entry on Ted Kaczynski. That entry has (too) many great links, though I would especially encourage checking out this short article toward the end of this link entitled "The Death Penalty Up Close and Personal" by David Kaczynski (Ted's brother). Also worth a read is this 1999 article from Time magazine by Stephen Dubner.

Though I have given this sort of assignment to prior classes, I must note that this "case" has a disturbing new element. As detailed in this press report from July 2011, "Anders Behring Breivik, the suspect in Norway's twin attacks that killed at least 93 people, appeared to plagiarise large chunks of his manifesto from the writings of Theodore Kaczynski." Here is more:

The 32 year-old appears to have quoted verbatim large sections from the preaching of Theodore Kaczynski in his 1500 page online rant. Breivik had “copied and pasted” almost a dozen key passages from the 69 year-old’s 35,000 manifesto, only changing particular words such as “leftist” with “cultural Marxist”.

It remains unclear what his motivations were, but experts said it appeared he had taken “inspiration” from Kaczynski whose two decade parcel-bomb terror campaign killed three people and 29 injured others.

Despite meticulous university thesis-style referencing through the manifesto, Norwegian bloggers discovered that passages quoting Kaczynski were not credited…. It was published on the internet just hours before he killed at least 93 people and wounded nearly 100 more in twin attacks in Norway.

Ragnhild Bjørnebek, a researcher on violence for the Norwegian Police Academy, described the disclosures as “very interesting” and showed startling similarities between the two terrorists. “The Unabomber was very intelligent and who was also a person that was very difficult to detect,” she told Norwegian media.

-

I suggested in class some time ago that you should read (and re-read) Furman thinking about which of the nine Justices' opinions you would have been most likely to join (assuming you had been a hypothetical additional Justice in 1972 and could only join an opinion rather than write your own). Because I suspect we will not have enough time in class to discuss all the opinions in Furman, I wanted to created this blog space to allow/encourage folks to weigh in on which of the opinions they found most convincing or compelling.

UPDATE on 9/16: Though she presumably did not indicate which of the Furman opinions she liked best, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg made some comments during a law school speech this week (as reported here) which suggest she is quite fond of what was the outcome in Furman and would like to get four more votes among the Justices on the current Supreme Court to once again halt death sentencing.

-

As you all should know, every student is required to submit a short paper (of no more than 5 pages) before Fall Break concerning a topic of sentencing law, policy or practice that you believe is under-reported and/or under-researched and/or under-litigated. I emphasize the "you" in this post because I want and expect this first paper will reflect your personal perspective on an issue of sentencing law, policy or practice that you believe should be getting more attention from the press and/or from researchers and/or from courts.

There are truly thousands of sentencing issues that I personally think merit a lot more attention from the press and from researchers and from courts. That reality is part of the reason for this assignment so that I can hear from interested students about what specific issues you personally consider problematically under-reported and/or under-researched and/or under-litigated. The best papers will not be trying to guess at what issue(s) I think merit more attention, but rather will be effectively explaining in clear and cogent terms the author's views.

Critically, at least some basic research may be required for you to confirm your beliefs as to what topic of sentencing law, policy or practice is under-reported and/or under-researched and/or under-litigated. In addition, the best discussion of this issue may explain not only why this issue deserves more attention, but also why you think the issue has heretofore not gotten the attention it deserves from the press and/or from researchers and/or from courts.

Make sense?

-

Though I spent probably too much class time Thursday referencing parts of the history of the death penalty in the United States, I do not think it is possible for students of modern sentencing law and policy to spend too much time reflecting on this history. I encourage all students to read up on the United States' history with the death penalty from various sources, such as the full opinions in Furman or the abolitionist-oriented account provided here by the Death Penalty Information Center or this reader-friendly review of DP history in the US .

Though I spent probably too much class time Thursday referencing parts of the history of the death penalty in the United States, I do not think it is possible for students of modern sentencing law and policy to spend too much time reflecting on this history. I encourage all students to read up on the United States' history with the death penalty from various sources, such as the full opinions in Furman or the abolitionist-oriented account provided here by the Death Penalty Information Center or this reader-friendly review of DP history in the US .One key historical point I sought to stress in class is that, though the US Supreme Court has been very involved in death penalty regulation through interpretations of constitutional law over the past forty years, during the prior 180 years the Supreme Court had relatively little to say on the topic. But this reality of Supreme Court relative lac of involvement in this historical story certainly was not a result of a relative lack of use of the punishment, because according to the ESPY File of all US executions, in the United States there were:

- 13 executions in 1790, the year after the US Constitution was ratified

- 8 executions in 1804, the year after Marbury v. Madison was decided

- 39 executions in 1869 the year after the 14th Amendment was adopted

- more than 100 executions in 1906, the year after the famous "activist" Lochner decision

- more than 1500 executions during the 1930s (roughly 3 each and every week)

Notably, when the US Supreme Court during the Warren Court years started getting much more actively involved in regulating state police and prosecution practices, lower state and federal courts did start more actively reviewing state death sentences. As a result, from 1967 to 1976, the period leading up to and around the McGautha and Furman and Gregg rulings, there were zero executions in the United States.

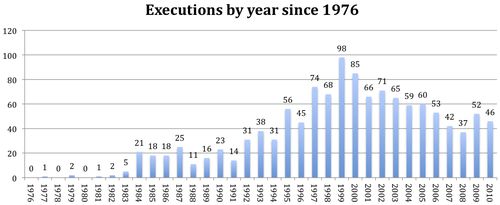

The Gregg ruling in 1976 is often used to mark and define the start of the "modern" death penalty era in the United States, and the chart from the DPIC reprinted above (and easier to read at this link) details that the US has been averaging more than 50 executions per year over the last two decades, with a recent one-year high of 98 executions in 1999 and a recent one-year low of 37 in 2008.

Lots of legal and non-legal factors have had an impact on these historical data, and one would struggle to come up with any simple explanation for precisely why our nation has had a roller-coaster, up-and-down experience with executions. Nevertheless, in addition to being factually interesting, I think there are various sentencing law and policy lessons to be taken away from this history. I am interested to hear student insights as to these possible historical lessons: do folks think this history suggests it is inevitable that the US will always be a death penalty nation, or that this history shows that the US has and could get along without many or even any executions?

Comments on what lessons we should take away from this history, and on what else is worthy of historical note and discussion here, are highly encouraged. Also, I encourage thoughts about whether the total number of death sentences or capital prosecutions (rather than just actual executions) would be important data in this historical story.

-

We ended class with a question/issue/talking-point that may well haunt us throughout the semester and that has arguably haunted all modern legal debates over modern issues of crime and punishment: is "death" really different as a matter of constitutional law?

Couple of preliminaries as we unpack this question/issue/talking-point going forward:

1. As a basic normative and empirical and factual matter concerning state punishment generally, the (too) simple assertion that "death is different" cannot be readily gainsaid. John Stuart Mill in his renown “Speech in Favor of Capital Punishment” (worth reading and available here), observed punishment of death makes a unique "impression on the imagination" and "is more shocking than any other to the imagination." The undeniable reality that death as a punishment "feels" different in kind than any other form of punishment necessarily means humans will react and respond to this punishment differently even if we try to treat it like any other form of punishment.

2. As a basic historical and descriptive matter concerning state punishment generally, the observation that "death is (and always has been) different in criminal law's doctrines and practices" also cannot be readily gainsaid. Much of both the common law history of criminal law's development, as well as much of modern statutory and related criminal punishment doctrines, reflect the reality that the people who make the law and shape its application "feel" differently about the death penalty than about any other form of punishment.

3. As a basic matter of constitutional text, the doctrinal basis for asserting that special substantive and/or procedural constitutional rules should control the death penalty is a pretty hard argument to make. The Fifth, Sixth and Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments contain nearly all the constitutional provisions and prohibitions that get the most attention in litigation over the death penalty (and other punishments), but the text of these provisions do not appear to call for many (or any) unique doctrines just for the death penalty.

With this background, I am eager to hear via comments or in class whether and how one can develop a strong argument for the claim that the Constitutionjustifies or demands or even allows special substantive and/or procedural constitutional rules for the operation and application of the death penalty. Putting this point a little differently, I think the easiest way to understand (and justify?) the pro-prosecution outcomes in cases like Williams and McGautha and McClesky comes from understanding that the justices in those cases were (justifiably?) concerned that any pro-defendant constitutional rulings would subsequently have to get extended to all non-capital cases and defendants.

-

I mentioned in class my belief that if we had truly conclusive and indisputable empirical evidence that using the death penalty to sentence/execute guilty murderers indisputably saves innocent lives, then there would be very little political and social debate concerning using the modern death penalty to sentence/execute guilty murderers. Does anyone want to take issue with this claim? Specifically, does anyone wish to argue that, even in the face of truly conclusive and indisputable that abolishing the modern death penalty would cost some innocent lives, that we still should get rid of the death penalty?

Critically, as revealed by reports at this pro-death penalty website and responses at this anti-death penalty website, there plainly is not clear empirical evidence that using the death penalty to sentence/execute guilty murderers saves innocent lives. Thus, one might reasonably accept my contention and still categorically oppose the death penalty given the current (and perhaps inevitable) absence of conclusive empirical evidence. Still, I want to have a discussion — here on the blog and/or in class — concerning my basic assertion that conclusive empirical evidence here could end what is often cast as a purely moral debate.

UPDATE: Inspired in part by the many thoughtful and effective responses to my initial inquiry, I am going to sharpen the hypothetical and see if the responses stay the same.

Let's suppose that we now have truly conclusive and indisputable evidence that the summary execution of Osama Bin Laden served to very significantly reduce the number and scope of terrorist attacks in the Middle East and around the world (including attacks being planned for the US), whereas the capture and continued confinement of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed has served to very significantly increase the number and scope of terrorist attacks in the Middle East and around the world (including attacks being planned for the US).

If we did have truly conclusive and indisputable evidence that OBL's quick execution saved many innocent lives in the US and around the world while KSM's capture and likely life imprisonment has cost many innocent lives in the US and around the world, do you think persons with moral opposition to the death penalty would still want all major terrorist suspects handled like KSM rather than like OBL? (Ignore, for purposes of this hypo, that KSM was waterboarded, though maybe that makes it easier to accept my supposition that how the US has dealt with KSM has cost more lives than how the US dealt with OBL.)

Steve D. gets to the heart of my inquiries here when he states that "only someone who bases their morality on pure utilitarianism would be swayed by such evidence," but he then claims that "most people are not utilitarians." I have the contrasting belief that everyone is a utilitarian if and when — and perhaps only if and when — the stakes get high enough and the empirical evidence is conclusive. And I think this is a critical issue to explore at the outset of any death penalty discussions becausemany people on all sides of the DP debate are often (1) quick to assert that nothing is more valuable/important than innocent lives, and (2) eager to claim that they have strong (but not conclusive) empirical evidence to support their DP position(s).

-

In addition to closely reviewing the 1949 Williams v. New York case (which can be read in full here and is worth the time to read in full), we will discuss in class on Thursday which particular institutional players tend to exercise the most formal and informal sentencing power, and whether and how you think these institutional players should have their powers limited and regulated. Long story short: legislatures, prosecutors, trial judges, and parole/prison officials have historically wielded the most sentencing power, but many modern reforms have given larger roles to sentencing commissions and appellate judges.

Here (and perhaps also in class), I am eager to look at this issue from the other side of the equation: that is, I want to hear whether and why you might think certain institutional players should have little or no formal or informal sentencing power. Again, history is somewhat instructive: victims, police, juries (except in capital cases) and appellate judges have historically wielded little sentencing power, but many modern reforms have given larger roles to victims and appellate judges.

As we will discuss, every institutional player that actively seeks to be involved in the sentencing process usually can have some input or impact. But that practical reality should not prevent a sentencing system (or us) from exploring how to limit the authority of those players we believe should have the least power to impact sentencing outcomes. (There are lots of general reasons why we might want to limit and/or regulate a particular player's sentencing power: e.g., we fear that particular institutional player has a certain problematic/systematic bias, or will too often pursue a disfavored punishment purpose or form, or will be too subject to undue influences by other actors, or will make inconsistent or less-than-thoughtful decisions.)

So, who do you think should have the least sentencing power? Why?

-

We concluded our first week's class discussion with questions about whether and why castration (either physical or chemical) could and would be a fitting punishment for convicted rapist Richard Graves. As a preview of second week topics, I encouraged considering whether answers to these questions might be changed or significantly influenced if (a) Graves' victim urged this punishment, and/or (b) Graves himself embraced this punishment (perhaps in lieu of additional years in prison).

For those with a visceral negative reaction to castration as a form of punishment, I suggest reflection on Michel Foucault's astute insight that, in modern times, we seem far more content to "torture the soul" through long terms of imprisonment than to "torture the body" through physical punishment. In addition, for those with a legalistic negative reaction that the US Constitution would never permit such a punishment, I suggest reflection on the fact that few forms of punishment have ever been the subject of Supreme Court review.

Moreover, for anyone drawn to an originalist approach to constitutional interpretation, a fascinating document authored by Thomas Jefferson suggests at least some Framers approved and endorsed castration as a punishment for some crimes. This Jeffersonian document, titled "A Bill for Proportioning Crimes and Punishments," includes these notable passages:

Whereas it frequently happens that wicked and dissolute men resigning themselves to the dominion of inordinate passions, commit violations on the lives, liberties and property of others, and, the secure enjoyment of these having principally induced men to enter into society, government would be defective in it's principal purpose were it not to restrain such criminal acts, by inflicting due punishments on those who perpetrate them; but it appears at the same time equally deducible from the purposes of society that a member thereof, committing an inferior injury, does not wholy forfiet the protection of his fellow citizens, but, after suffering a punishment in proportion to his offence is entitled to their protection from all greater pain, so that it becomes a duty in the legislature to arrange in a proper scale the crimes which it may be necessary for them to repress, and to adjust thereto a corresponding gradation of punishments.

And whereas the reformation of offenders, tho' an object worthy the attention of the laws, is not effected at all by capital punishments, which exterminate instead of reforming, and should be the last melancholy resource against those whose existence is become inconsistent with the safety of their fellow citizens, which also weaken the state by cutting off so many who, if reformed, might be restored sound members to society, who, even under a course of correction, might be rendered useful in various labors for the public, and would be living and long continued spectacles to deter others from committing the like offences.

And forasmuch the experience of all ages and countries hath shewn that cruel and sanguinary laws defeat their own purpose by engaging the benevolence of mankind to withold prosecutions, to smother testimony, or to listen to it with bias, when, if the punishment were only proportioned to the injury, men would feel it their inclination as well as their duty to see the laws observed.

For rendering crimes and punishments therefore more proportionate to each other: Be it enacted by the General assembly that no crime shall be henceforth punished by deprivation of life or limb except those hereinafter ordained to be so punished….

Whosoever shall be guilty of Rape, Polygamy, or Sodomy with man or woman shall be punished, if a man, by castration, if a woman, by cutting thro' the cartilage of her nose a hole of one half inch diameter at the least….

All attempts to delude the people, or to abuse their understanding by exercise of the pretended arts of witchcraft, conjuration, inchantment, or sorcery or by pretended prophecies, shall be punished by ducking and whipping at the discretion of a jury, not exceeding 15, stripes….

I highly encourage everyone to read the entire Jefferson punishments bill: it provides not only a perspective on crime and sentencing at the time of the Founding, but it also spotlights the array of punishments used before the birth of modern prisons.

-

Issues of race and gender arise throughout the criminal justice system and their impact on sentencing outcomes is often a subject of great debate and controversy. In addition to encouraging you to consider the linkages between theories of punishment and race/gender issues, over the next few classes we will explore in various ways the relationships between sentencing discretion, disparity and discrimination.

Though there is (too) much to say on all these matters, I thought it useful in this forum to encourage focused consideration of these matter in two distinct contexts: the imposition of the death penalty for murder and the federal prosecution and sentencing of child pornography offenses.

Death Sentencing: As you may know, the death penalty is often criticized for having a racial skew, and pages here and here from the Death Penalty Information Center provide lots of data and reports on this front. One of many statistics on these pages I find notable is that out of roughly 1250 persons executed in the US in the modern era, more than 250 black defendants have been executed for killing white victims, but only 16 white defendants have been executed for killing back victims.

Far less frequently discussed are the apparent gender disparities in the application of the death penalty in the United States, though this page from the Death Penalty Information Center and this report from Professor Victor Streib provides coverage of this issue. The data from these sources reveals that women account for about 10% of all murder arrests, but that women make up less than 2% of death rows (55 / 3,261) and less than 1% of those executed (12 / 1,250+). Indeed, in the last 8 years, nearly 450 men have been executed, while only 2 women have been executed (0.45%).

Federal Child Porn Prosecutions: Federal sentencing for child pornography offense is a hot topic, in part because the number of prosecutions and the length of sentences imposed for these offenses has increased dramatically over the past decade. What is rarely discussed, however, is the disproportionate involvement of white men in these cases, especially relative to the the general federal offender population. The latest federal data from the US Sentencing Commission is in this report which provides a detailed racial and gender breakdown for offenders in each primary federal offense category (Tables 23 and 24 at pp. 44 and 45 of the pdf).

Roughly speaking, when immigration offenses are excluded (because 90% involve hispanic offenders), the general population of federal defendants sentenced is about 1/3 white, 1/3 black and 1/3 hispanic. But for child porn offenses, the sentenced defendants are almost 90% white and only 3% black and 6% hispanic. Similarly, the general population of federal defendants sentenced is about 85% male and 15% female. But for child porn offenses, the sentenced defendants are over 99% male and less than 1% female.

Do you find these data surprising? disturbing? What additional information would you like to have in order to make a judgment concerning these data?

-

Welcome to the THIRD re-launch of this blogging adventure. This blog started over four years ago (with the uninspired title of Death Penalty Course @ Moritz College of Law) to facilitate student engagement in the Spring 2007 course on the death penalty that I taught at OSU's Moritz College of Law.

Though I closed this blog down not long after that course ended, I was pleased to see all the students' hard work as reflected in the archives still generating significant traffic and much of the posts remain timely. Consequently, as when I geared up for teaching Criminal Punishment & Sentencing in Spring 2009 at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law and again when visiting in Spring 2010 at Fordham School of Law, I decided to reboot this blog to allow the new course to build indirectly in this space on some of the materials covered before. In all of these classes, I was generally pleased with how this blog helped promote a new type of student engagement with on-line media and materials. (For the record, OSU students engaged with the blog much more and better with Fordham students.)

Now, circa August 2011, I am gearing up for teaching Criminal Punishment & Sentencing again. Because we have a traditional text for our 2011 class, I am not yet sure how much of a role this blog will play in course activities. But, especially because a lot of new exciting sentencing developments seem likely in in the weeks and months ahead, I suspect this space will stay active just by trying to keep up with current events (as well as as a place to post information about class activities and plans and assignments).

WELCOME!

————————————————————-

————————————————————-

————————————————————-

UPDATE: The on-line supplement referenced in the course description is available at this link.

————————————————————-

-

Though this blog space has not been especially active through the semester, I wanted to do a (last?) post to share some concluding thoughts:

1. I first wanted to say thanks to all of you for taking a chance by signing up for a seminar with a visiting professor, and also for sticking with the class after it surely became clear to you that I am somewhat unorthodox in my approach to teaching and student engagement.

2. I really meant it when I said that anyone who has survived my seminar has an open (and essentially permanent) offer to work with me on my various research projects and/or pro bono practice activities. Though I cannot always ensure you get paid for your time and energies, I can always ensure that you will have interesting (and generally low-stress) work opportunities. Especially because modern technology makes it easy to work together on-line from different cities (or even different countries), you should keep in mind that there is significant sentencing work to be found in Berman's office even if you are nowhere near Berman's actual office.

3. I hope you will consider using the comments to this post (as well as the traditional course evaluations) to share any final reflections you have about either the substance or the style of our course and the assignments you have been asked to complete. My own reflections include the fact that I found every moment that we spent together in class to be wondrously engaging and productive, and yet I still feel as though I barely scratched the surface concerning all the sentencing themes, issues and doctrines that I had hoped to cover. (In addition, I am truly quite grumpy that SCOTUS did not issue opinions in any of the major sentencing cases of the current term while we were still together.)

4. As this post reveals, I remain eager for continued engagement with all of you, not just concerning our course, but also concerning your futures and plans. Please do not hesitate to keep in touch with me via e-mail, and be extra sure to connect with me if/when you are looking for any professional opportunities in the sentencing arena.

5. Good luck finishing up you white papers and the rest of this semester.

-

This post is intended to provide a place and space for questions about the final white-paper assignment. I will, of course, answer questions about the assignment in our final class and via personal e-mails, but I encourage students to feel comfortable asking questions here so that I can provide answers to questions in a forum that should remain accessible to all through the exam period.

-

As mentioned in class last week, our last Wednesday together this semester is packed full of exciting activities. As mentioned before, I have arranged for US District Judge John Gleeson to come speak with our class, and we are meeting at for breakfast an hour before our class time at the diner on 10th Avenue. Students are welcome and encouraged to join this morning pre-class meeting (and no sign-up is required).

In addition, after class I am planning to attend (and along with up to 5 students) a special "lunch and learn" event with the new US Attorney for the District of New Jersey, which is taking place at a midtown law-firm starting at 12:30pm. Students interest in taking this little "field trip" are urged to indicate their interest below ASAP so that I can send a list of names of attendees to the event organizers.

-

I have arranged for US District Judge John Gleeson to come speak with our class on our final day together (next week, April 28), which means this coming week is essentially our last opportunity to cover formally in class any topic or topics that you are especially eager to discuss. For that reason, I hope students will use the comments to this post as an opportunity to indicate any and all substantive or procedural sentencing topic(s) that should be on our agenda for our closing time together.

As always, I have plenty of topics/ideas in mind, and I am also hopeful (but not at all confident) that we might finally have a hot new SCOTUS sentencing ruling to discuss this week (as the Justices have announce that new opinions will be handed down on Tuesday and Wednesday mornings). But I want to make extra sure we devote time to any topic that students are still eager to have formally covered in the classroom.

-

Though not always called a white-paper, all the of documents linked below are examples of the kinds of policy documents I have in mind for the final class paper:

- New ACS issue brief on felon disenfranchisement

- New ACS paper on racial disparities in the death penalty

- New ACS issue brief making the case against juve LWOP

- Two new reports from The Sentencing Project about state prison reductions

- New report from The Sentencing Project on the drug war's racial dynamics

- New HRW report assailing juve LWOP in California

- LDF report documents disparities in juve LWOP in Mississippi

- New report on juve LWOP in Massachusetts